We (finally) made it to the end of the sixth chapter of The Gospel of John. Our reading began with the disciples and followers of Jesus asking questions we have echoed over the past six weeks. Namely, “WTF Jesus!?”

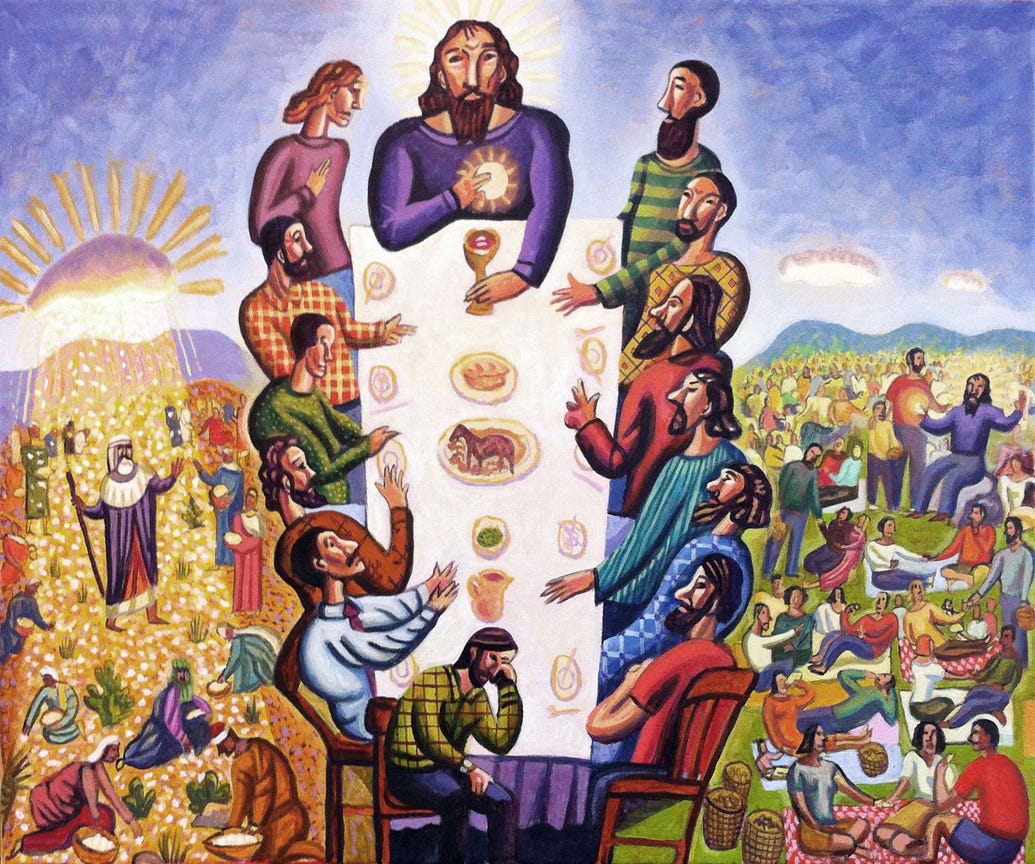

Sometimes, the Scriptures just hit you differently. I can imagine the congregation in the synagogue in Capernaum sitting there, nodding along, until they heard what he said. “Eat my flesh, drink my blood.”[i] How could they not be confused? Even the disciples, when alone with Jesus, had to ask him, “What is this all about?” And John tells us that many of Jesus’ disciples no longer followed him after this scene. These are tough words to swallow.

The Gospel of John begins beautifully with, “In the beginning was the Word, and the Word was with God, and the Word was God. He was in the beginning with God.”[ii] And, “And the Word became flesh and lived among us.”[iii] But now, Jesus’ words have moved from beautiful, spirit-filled sentiments to something with more bite and uncomfortable – “The Word became meat and dwelled among us.”[iv]

The disciples speak for us when they ask, “This teaching is difficult; who can accept it?”[v] But Jesus does not back down. “Does this offend you?”[vi] he asks. Then, Jesus doubles down, “The words that I have spoken to you are spirit and life.”[vii] You can almost hear the challenge in Jesus’ voice. Maybe that is the point of these strange words – they’re meant to shake us up.

Rev. Fleming Rutledge writes about the scandal of the cross – the idea that the central symbol of our faith is an instrument of torture and execution. She writes, “The crucifixion is irreducibly disturbing. It cannot be domesticated. It resists our attempts to make it appear palatable. ” In the same way, Jesus’ words here are intended to disturb us, to resist our attempts to smooth over the rough edges of our faith. Jesus is pushing us outside our comfort zones because that is where real transformation happens.

It reminds me of driving past or walking through Arlington National Cemetery. You pass by the endless rows of white headstones, symbols of sacrifice and service, but if you’re not careful, they can become just another part of the landscape. It takes something jarring, something that forces you to stop, to make you really see them again, to remember what they stand for. Standing at the Tomb of the Unknown Soldier, watching the changing of the guard, you can’t help but be confronted by the solemnity of it all—the honor, the respect, the weight of history. Only when you stop and allow yourself to be confronted by the reality of what this place represents do you begin to understand its significance.

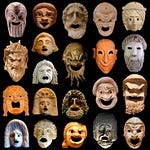

Author Flannery O’Connor once said that she used strange and freakish characters in her stories because modern readers have a self-protective crust around them, and only something extraordinary can break through. Maybe that is what Jesus was up to – cutting through the crust. Jesus challenges our assumptions, forcing us to confront the reality of who he is and what it means to follow him.

Modern life can make us numb. We are constantly bombarded by advertising on our phones, the 24-hour news cycle, and the endless scroll of social media. The noise is relentless. It is easy to shut down and disconnect from the world around us. Think about the last time you were riding Metro – everyone is glued to their screens, lost in their own world, tuning out everything else. It has become second nature to disengage, to just go through the motions.

During the Cold War, psychiatrist and author Robert J. Lifton called this “nuclear numbness.”[viii] Today, maybe it’s “digital numbness.” We have become experts at disengaging. Sometimes, it feels like modern life is too invasive, and the only defense is to shut down and stop paying attention.

But Jesus calls us to do the opposite. John Wesley believed that the Christian life was a continual growth and engagement journey. The founder of the Methodist movement said, “Give me 100 preachers who fear nothing but sin and desire nothing but God, and I care not a straw whether they be clergymen or laymen; such alone will shake the gates of hell and set up the kingdom of heaven on earth.” For Wesley, to follow Jesus requires active participation and a willingness to be challenged and to challenge others.

There are people in our community – our family, friends, neighbors, co-workers, and classmates – who are so overwhelmed by everything happening around them – work, school, politics, and even the hustle of daily life – that they have withdrawn. They have built walls and turned off their emotional circuits because it all feels like too much. But in doing so, they miss out on life and real connections. Wesley would remind us that disengagement is not an option for Christians. We are called to be in the world, to engage fully, even when it is uncomfortable.[ix]

Living in Northern Virginia, we are surrounded by people who have become experts at keeping things at a distance and maintaining the “high ground” of detachment. We see it in the way we talk about politics, about the issues of the day, and about our faith. Everyone’s got a take, but nobody wants to get too involved. It is safer that way, but it is also lonelier.

Jesus, though, calls us to something deeper. Plato said you can only really learn that which you are willing to fall in love with. That is the challenge for us. When was the last time you fell in love with something – really invested yourself in it? Whether it is your neighborhood, your work, or even your faith, real learning real living, requires that commitment.

Here’s a practical example: next time you are at a Nationals game (or better yet, an Orioles game) or taking a stroll along the National Mall or through your neighborhood, do not just pass through. Take a moment to see the people around you, notice the beauty of the city and your neighborhood, and appreciate the history you are walking through. Engage with it. Let it change you. Wesley was talking about this when he emphasized the importance of being present in the moment, of fully engaging with our living God and the world around us.

This brings us back to Jesus’ challenging words. The disciples were confused, even offended. But they also recognized something in Jesus they could not find anywhere else. As Peter said, “Lord, to whom can we go? You have the words of eternal life.”[x]

In a moment, we are going to pray. I invite you to close your eyes and pay attention. You see, something the world is trying to keep from you is this: our unconsciousness is so deeply entrenched that consciousness has become downright heroic. That is one reason why we gather on Sunday mornings to worship. We read these verses from an ancient book and give you music you will not find on the radio or social media. Many call it “going to church” or something to check off the to-do list. But I want to call it something else. Let’s call it trying to see. Let’s call it practicing paying attention to the presence of the living God among us, here in Arlington, in McLean, in DC, and in our lives.

John Wesley once said, “The best of all is God is with us.” That is the truth we are trying to hold on to, the truth that can get lost in the noise and distractions of modern life. But it is a truth worth listening to, waking up for, worth living for. People, would you pay attention?

Amen.

[i] John 6:54, NRSV

[ii] John 1:1-2

[iii] John 1:14

[iv] John 1:14, as interpreted through John 6

[v] John 6:60

[vi] John 6:61

[vii] John 6:63

[viii] Robert J. Lifton, Indefensible Weapons: The Political and Psychological Case Against Nuclearism (New York: Basic Books, 1982), 45.

[ix] Rod Dreher's Benedict Option advocates for Christians to withdraw from mainstream culture in order to preserve and nurture their faith communities. While Dreher's call for intentional, countercultural Christian living is commendable, the proposal has significant limitations. It risks retreating from the very world that Christians are called to engage. The New Testament clearly teaches that believers are to be "in the world, but not of the world" (John 17:14-18). This implies active participation in society, even when it is uncomfortable or challenging.

Jesus modeled engagement with the world through his interactions with diverse individuals and communities, often in situations that were far from comfortable or safe. The Great Commission (Matthew 28:19-20) further compels Christians to go out into the world, making disciples of all nations, which inherently requires engagement rather than withdrawal.

Moreover, history shows that the Church has often been most transformative when it has remained engaged with society, offering a prophetic voice and practical witness in times of cultural upheaval. While Dreher rightly identifies the challenges of maintaining Christian identity in a secular age, his approach may inadvertently diminish the Church's role in being salt and light (Matthew 5:13-16) to a world in need of redemption.

In short, while the Benedict Option raises important questions about the nature of Christian community in a post-Christian society, it ultimately falls short by emphasizing withdrawal over engagement. Christians are called to be fully present in the world, embodying their faith in every sphere of life, even when it is uncomfortable.

[x] John 6:68

Share this post