Gracious and holy God,

we come to you this morning with just enough self-righteousness to think this passage isn’t about us.

We’ve convinced ourselves we’ve never murdered anyone, though we’ve certainly canceled a few people in our hearts.

We’ve managed to stay out of the tabloids, but not always out of trouble.

And we’ve loved your law right up until it got personal.

So, before we open your Word, interrupt our pride.

Interrupt the little narratives we tell ourselves that let us off the hook.

We didn’t show up today to be made comfortable.

We came to be made whole.

Give us ears to hear your mercy in the middle of your judgment.

Give us hearts soft enough to be changed, even when we’d rather be left alone.

And if we walk out of here today a little more honest, a little more free,

we’ll know you’ve been at work among us.

We ask this in the name of the one who loved us too much to leave us as we are—

Jesus the Christ.

Amen.

Well, I’ve got to say I wish we could’ve kept Mack, our now former seminary intern, for just one more week. This passage would’ve made an excellent “learning experience” for him. What better way to test your call to ministry than being handed a sermon with murder, lust, and divorce in it? If you can survive this text without running for the hills—or at least back to seminary housing—you’re probably in the right vocation.

But here we are. And maybe the real surprise is that Jesus isn’t trying to make it easier for anyone—not the intern, not you, and definitely not me.

We often read this section of the Sermon on the Mount like a list of unrelated warnings:

Don’t be angry.

Don’t lust.

Don’t get divorced.

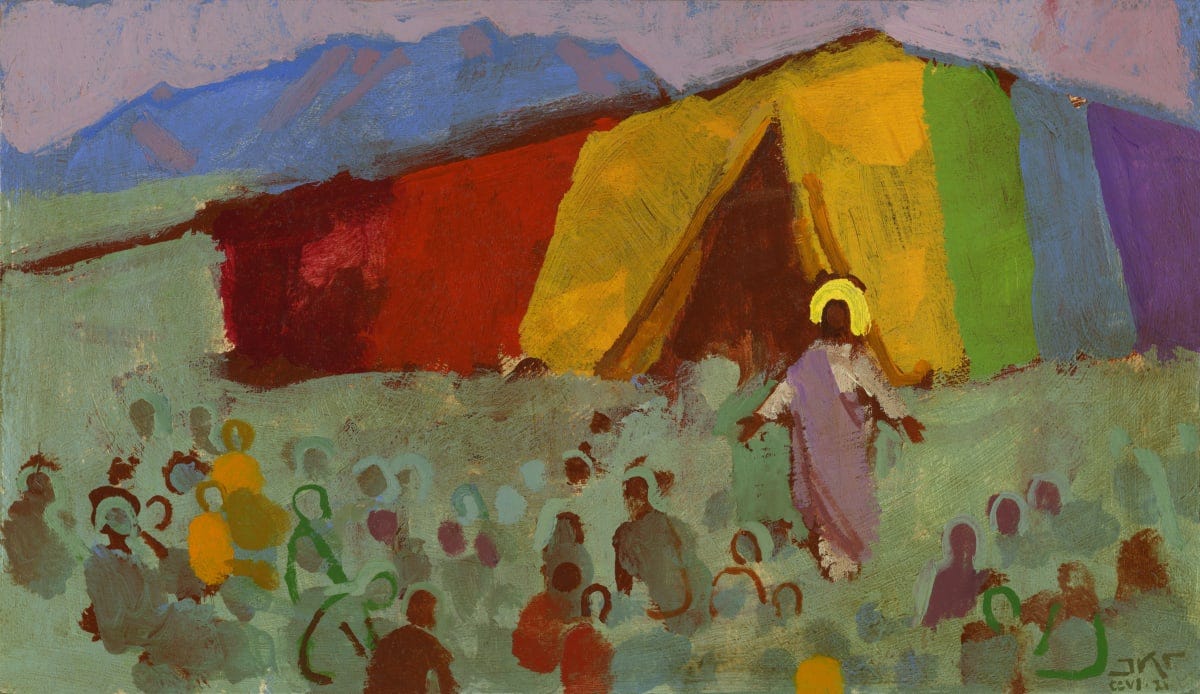

But Jesus isn’t giving a TED Talk on hot-button issues. He’s casting a vision—a resurrection-shaped way of being human. This is not about sin management or moral behavior modification. This is about wholeness. About the kind of healing only God can do—not just in your habits, but in your heart.

You don’t go to the Sermon on the Mount for advice.

You go to get undone and put back together.

So let’s stop treating these as separate issues and hear what Jesus is really saying:

“You don’t have to live fractured anymore. The kingdom of God can make you whole.”

Whether Jesus is talking about anger, lust, or divorce, he’s addressing the same core sickness:

We treat people like they’re disposable.

We get angry, and suddenly that person doesn’t deserve our grace.

We lust, and that person becomes a fantasy rather than a human being.

We divorce (in Jesus’ context, especially men divorcing women), and someone gets thrown away like a used napkin.

And Jesus says: That’s not how it works in my kingdom.

The resurrection is God’s definitive declaration that nobody is disposable.

Not the ones we’re angry at.

Not the ones we’ve objectified.

Not even ourselves when we’ve failed.

“You have heard it said: ‘You shall not murder.’ But I say to you…”

Most of us don’t need to be told not to murder people. We’re doing okay there. But Jesus says the real problem isn’t murder—it’s the inner rage, the simmering bitterness that slowly writes people out of our hearts. You don’t need a weapon to kill someone. All it takes is the decision that they don’t matter anymore.

Jesus says if you remember someone has something against you, leave your gift, go make peace.

He’s saying: Don’t come offering me praise if you’re still nursing a grudge.

Because in the Kingdom of God, reconciliation is more important than religion.

Then Jesus turns to lust. Again, not just about the act of adultery, but the inner narrative—the look, the objectification, the fantasy that strips away someone’s dignity.

Lust isn’t about desire—it’s about desire without connection, covenant without commitment. It’s desire without resurrection. It’s wanting something at the expense of someone else’s full humanity.

Jesus isn’t shaming you for having a body or for being human. He’s saying:

You don’t have to keep seeing people as means to your ends. There is another way to look at someone—through the eyes of Christ’s resurrection.

And then, Jesus speaks about divorce—not to condemn those who’ve already been hurt by it, but to confront a culture where relationships were disposable, especially for women.

In Jesus’ day, a man could write a certificate of divorce for almost any reason. She burned dinner? She’s out. And Jesus says: No. Marriage is not a loophole-ridden contract—it’s a covenant. You can’t throw someone away just because they stopped making you happy.

Let’s be clear: Jesus is not here to load shame on folks who’ve been through the pain of divorce. Some relationships die. Some needed to end for safety, sanity, survival. Jesus doesn’t shame the broken. But he does call out our impulse to treat people like products—things to be upgraded, returned, or tossed.

So what is Jesus really after?

Not perfection.

Not purity culture.

Not legalistic holiness.

He’s after wholeness that leads to holiness. He’s after a heart made alive again. A heart that doesn’t live out of bitterness, fantasy, or fear. A heart that’s been raised from the dead.

This is Eastertide, after all. We’re not just celebrating what happened to Jesus.

We’re living into what can now happen to us.

Jesus says, You don’t have to live angry. You don’t have to live consumed by lust. You don’t have to keep failing at love. There is resurrection wholeness for your fractured life.

Resurrection people don’t just follow rules—they see differently.

They look at their enemies and say, That’s someone God loves.

They look at their desires and ask, Does this make me more human, or less?

They look at their relationships and say, Covenant is hard, but it’s worth it.

Because resurrection people don’t settle for patched-up lives.

They want to be made new—from the inside out.

Share this post