Psalm 150, Matthew 5:1-12, and John 20:19-31

God of resurrection and costly grace,

we didn’t come here today expecting anyone to climb over pews,

to throw pride aside,

to break into weeping in front of people they’ve wronged.

We came looking for order,

for a few good words to steady us—

but you are the God who overturns the tables and empties the grave.

So before we get too comfortable—

interrupt us.

Interrupt our defensiveness, our fears,

our well-practiced habits of self-preservation.

If your Spirit can raise the dead,

then raise us too—

out of fear and into faith,

out of apathy and into love,

out of safe religion and into dangerous grace.

Speak, Lord.

And if it undoes us—so be it.

In the name of Jesus,

who walked out of the tomb and still walks toward us,

Amen.

A good pastoral rule of thumb: when multiple people in your congregation, more than you can count on one hand, send you the same article, read it. Don’t just skim it over and move on to the next thing—read it. Many of you sent me the same opinion piece by David French on Sunday afternoon and Monday. A gift to ease me into my long-awaited post-Easter nap. French is a political commentator, attorney, and author known for his thoughtful reflections at the intersection of faith, politics, and culture. The title of this article? Have You Ever Seen a Person Come Back to Life?[i] It is a catchy title for an Easter Sunday essay.

French is not talking about cemeteries emptying or dramatic scenes from real-life hospitals or TV dramas. He’s talking about those moments when the Holy Spirit does something believed to be impossible. Moments when someone who seemed too far gone turns back to life.

French recalls the story of a young man in his Kentucky church. This kid was every Sunday school teacher’s worst nightmare. French describes the young man as cruel, reckless, and hard-hearted. But one night, at a revival service, the young man got up. He did not wait for the aisle to clear. He stepped over pews to make his way to the front of the sanctuary. The young man knelt at the altar. As he knelt, who received him? Not a committee or usher inviting him to return to his seat. No, the very same people he had hurt.

They embraced him.

Met him with grace.

A resurrection moment.

It’s been a while since I have seen someone step over a pew, let alone over a pew to get to the front of the sanctuary. Its challenging enough to convince someone to sit in the front row. But here at Walker Chapel, I have seen reconciliations that have made me believe in miracles. Mercy extended in places where I was almost certain bitterness would win. I have seen apology and remorse in places where it seemed all but certain that stubbornness would prevail. And when I read French’s essay, I saw a glimpse of what Jesus lays out in the Beatitudes.

The Beatitudes are more than greeting card theology or aspirations. In the Beatitudes, Jesus is making an announcement—an unveiling of his kingdom, the world turned on its head where mourners are comforted, the meek inherit, and peacemakers get a front-row seat.

The kicker? Jesus is not handing out sentimentalities for Hobby Lobby to print on wall art. The resurrection guarantees that this is the way the world truly is and will be.

Jesus meant it.

He lived for it.

Died for it.

And in rising, Jesus guarantees it.

If you want to know what the Kingdom of God looks like, Jesus tells us to look for the people we usually overlook. Blessed are the poor in spirit, those who mourn, the meek, and the merciful.

Listen closely because Jesus is flipping the world’s script. What we have been told and what we have sold to others is turned upside down.

Our culture says, “Blessed are the confident.” Jesus says, “Blessed are the poor in spirit.”

“Blessed are the winners,” says the world. Jesus says, “Blessed are the meek.”

We think those who fight back are blessed, but Jesus says, “Blessed are the peacemakers.”

We have exhausted the power of the word “blessed.” We use the word as a throwaway. Blessed are we if we find a good parking space or receive a promotion. #Blessed. We print “Blessed” on cheap wall art while the people making it live and work in conditions no one would dare call blessed. Jesus is talking about something more disruptive. In Greek, it’s “makarios” (μακάριος) —a deep joy, a settled state of divine approval.

Not a feeling. An act.

Not for the obvious but for the ones who look like they are losing.

Dietrich Bonhoeffer taught these Beatitudes at the same time when blessing looked like goose-stepping with the crowd and keeping your head down. Bonhoeffer heard Jesus differently than his counterparts in the German Church. He heard a call to stand apart.

For Bonhoeffer, the Beatitudes describe the very shape of the life of a disciple. Not optional extras. Not a personality type. But a consequence of a call. Writing:

“With every beatitude, the gulf is widened between the disciples and the people. Their call to come forth from the people is inevitable.”[ii]

The world does not get it and will not applaud it. But Jesus does. Bonhoeffer reminds us that the church is not a club for the successful but a community for the broken, poor in spirit, merciful, and persecuted.

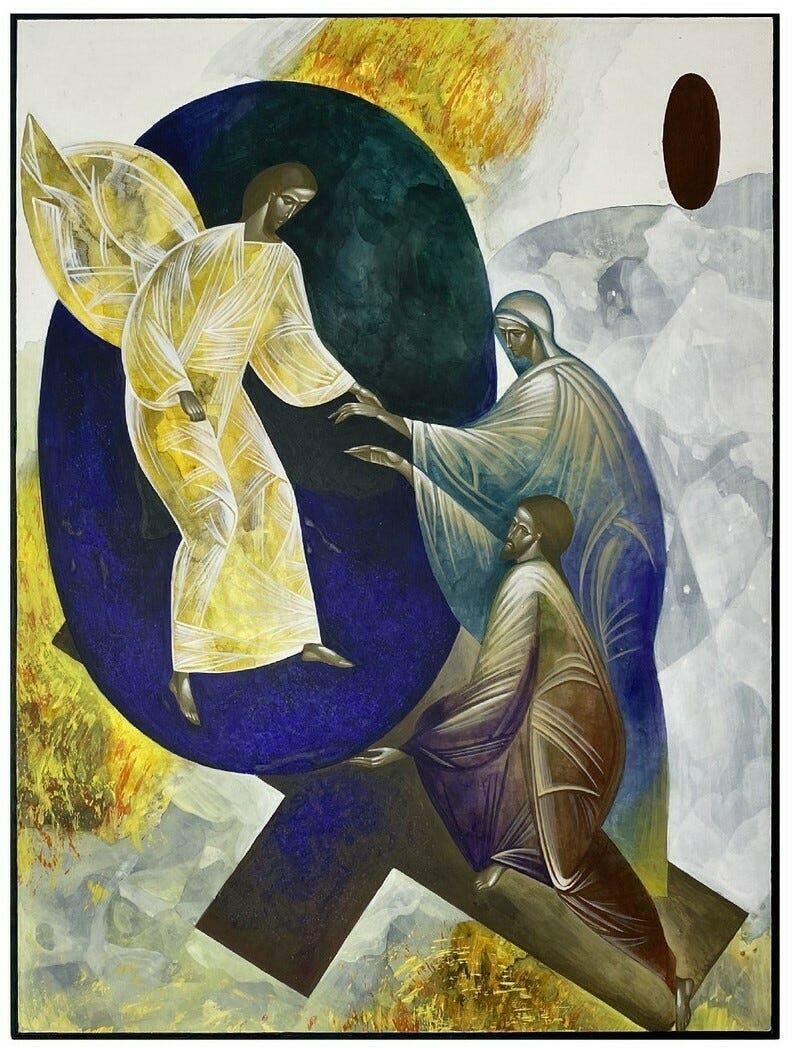

In the resurrection of Christ, we see just how right He was. Because when the world did its worst to Jesus—powers mocked him,[iii] crushed him,[iv] killed him[v]—God raised him up. Meaning, the Beatitudes are not just a list of noble-sounding losers. They are the resume of our resurrected Lord. A job description for His body, the Church.

Here’s what Easter does: it confirms that Jesus’ version of blessedness is not fantasy. It is divine mercy over vengeance, humility over ego.

And it forces us to choose: which kingdom do we believe is real?

The Revised Common Lectionary[vi] assigns the story of two disciples walking down a dusty road to a town called Emmaus for this Sunday. It’s a story of grief, confusion, and—eventually—recognition.

Jesus joins the two disciples on their journey, but they do not know it is him. They walk with Jesus. They talk with Jesus. They share their shattered hopes: “We had hoped he was the one to redeem Israel.” They say all the right things. They say Easter-y things. But they do not believe it yet.

They share a meal, and it is not until Jesus breaks the bread—that is when their eyes are opened. That is when they realize who’s been walking with them the whole time.

The resurrection does not always come with a trumpet blast. Sometimes it comes in a whisper. Sometimes it comes in the familiar act of grace—a broken loaf, a broken heart, a broken man stepping over pews to be made whole.

And sometimes, like those disciples, we do not recognize resurrection until it’s already happening. Until the bread is broken. Until the embrace is given. Until mercy interrupts us.

David French draws a line between two kinds of churches. The first is the “Fear the World” church. Always on the defense, suspicious. Always preparing for the next culture war. The second is the “Love Your Neighbor” church. Confident. Not because it has power but because it believes in resurrection. It moves toward suffering, not away from it.

The church living in the light of the resurrection is the one that opens its doors to the hurting. And people living in the light of the resurrection are the ones who embrace the man who climbed over the pews.

I am not naive. I know this does not make for easy living. You might get walked on. You will be misunderstood. You might be asked to forgive the very person you believe deserves it the least. But that is what the resurrection church does. It is what resurrection people do.

The Beatitudes are not there to make you feel guilty for not measuring up. Jesus’ words show us what grace looks like when it puts on flesh. To show us what living in the light of Easter looks like.

And, in a world obsessed with ladders, Jesus invites us to take the stairs down. Down into mourning. Into mercy. Into the mess because that is where resurrection happens. Not in the sanitized safety of success. Instead, in the places where everything seems lost. And let’s not forget—before Jesus walked out of that tomb, the Church teaches he descended into hell.[vii] [viii] [ix] That’s right. Into hell. He didn’t hover above the pain or sidestep the suffering—he went to the very bottom. Because that’s where the captives were. And if the resurrection means anything, it means there’s no pit so deep that Jesus won’t climb down to pull us out.

That is where God shows up and says, “Blessed are you.”

We are a “love your neighbor church,” a resurrection church because you are resurrection people.

It is not that you believe in a one-time miracle but rather live in the light of a whole new reality made possible through the stone-rolling power of God’s grace. We are not hanging onto vague spiritual sentiment. No, we have staked everything on the claim that Jesus was right—about God, us, and what it means to be blessed.

Our risen Lord calls us to lose ourselves for His sake in a world that tells us to protect ourselves at all costs. The empty tomb declares that true power is found in humility and true blessing in mercy. The resurrection does not just vindicate Jesus—it vindicates the whole upside-down Kingdom of God.

Do not walk away from the Beatitudes.

Do not water them down.

Do not wait for the world’s approval.

Live them as if Easter is the truest thing that ever happened.

Because it is.

Blessed are you who do.

Amen.

[i] French, David. “Opinion | Were You Raised in a Church That Fears the World or Loves Its Neighbors? - The New York Times.” The New York Times, 20 Apr. 2025, www.nytimes.com/2025/04/20/opinion/easter-christianity-jesus-trump.html.

[ii] Bonhoeffer, Dietrich. The Cost of Discipleship. Touchstone Simon & Schuster. 1995. Page 108.

[iii] Matthew 27:39-41

[iv] Isaiah 53:5

[v] Matthew 27:45-54

[vi] The Revised Common Lectionary is a three-year schedule of Scripture readings shared by many churches. It’s one of the church’s best attempts to ensure that we preachers do not just preach our favorites or skip the hard parts. Instead, it walks us through the full drama of God’s story—creation, covenant, exile, incarnation, crucifixion, resurrection, and the strange new world of the church. During Easter, the lectionary does not sprint past the empty tomb. It slows us down. Keeps us in a state of shock over the resurrection. That’s why the gospel text for the Second Sunday of Easter each year is not just a postscript—it’s the story of the risen Christ showing up, uninvited, to slow-walking, broken-hearted disciples on the road to Emmaus. The RCL makes sure we don’t miss that—because resurrection often shows up not in the sanctuary, but on the road.

[vii] The Apostles’ Creed, one of the Church’s earliest affirmations of faith, declares that Jesus “descended to the dead” (or “into hell,” in traditional phrasing). This line reminds us that before the risen Christ walked out of the tomb, he first went all the way down—into death itself—to liberate those held captive and proclaim victory in the darkest place.

[viii] Several scriptures echo this mysterious but hope-filled claim. In 1 Peter 3:18–20, we hear that Christ “went and made a proclamation to the spirits in prison.” Ephesians 4:9 speaks of him descending “into the lower parts of the earth.” And Acts 2:27–31, quoting Psalm 16, affirms that he was not “abandoned to Hades.” The early Church read these texts together as a picture of Christ’s saving work extending even into the realm of the dead.

[ix] Theologians have long called this moment “The Harrowing of Hell.” Far from a footnote, it is a crucial part of the story: Christ goes to the farthest depths so that no corner of creation lies outside his redemptive reach. As one ancient homily put it: “He has gone to search for our first parent, as for a lost sheep” (From an anonymous Holy Saturday homily, c. 4th century, often attributed to St. Epiphanius).

Share this post