“How long, O Lord? Will you forget me forever?

How long will you hide your face from me?

How long must I bear pain in my soul,

and have sorrow in my heart all day long?”[i]

Welcome to Lent. Today is the first Sunday in a forty-day journey toward the cross of Christ. A season full of self-examination and repentance; prayer, fasting, and self-denial; and reading and meditating on God’s holy word. As we make this journey, we know full well that the cross of Good Friday does not hold the last word, yet just as we cannot jump from Palm Sunday to Easter, we cannot jump from Ash Wednesday or the first Sunday of Lent to Easter. Our journey will be transformative; a continuation of the transfiguring Word of God.

We can expect to be transformed as individuals, but more importantly, we can expect to be transformed as Christ’s body. This journey will stretch us, moving us from complacency and complicity toward courage; courage to address our individual and corporate responsibility in the racial divide plaguing our communities and beyond.

We begin this Sunday with a psalm of lament.

“How long, O Lord? Will you forget me forever?

How long will you hide your face from me?

How long must I bear pain in my soul,

and have sorrow in my heart all day long?

How long shall my enemy be exalted over me?

Consider and answer me, O Lord my God!

Give light to my eyes, or I will sleep the sleep of death.”[ii]

The lament of the psalmist is a petition to God for God to address the distress experienced by the psalmist. Psalms of lament “tell the truth of the suffering that is smothering our worthiness, our dreams, our ability to work toward a better tomorrow,” writes Dr. Emilie M. Townes, Dean, and E. Rhodes and Leona B. Carpenter Professor of Womanist Ethics and Society at the Vanderbilt University Divinity School. Dr. Townes continues, “Naming these horrors in an unrestrained lament helps mold us into a people who respond with an emphatic ‘No!’ to the ways our nation and our communities of faith are turned into graven images of hatred and despair.”[iii]

None of us can pray the lament of a psalm without having our lament, our earnest prayers, added to those of the generations who have prayed these prayers before us and those who are praying with us now.[iv]

So, as the psalmist cried out generations ago, when we pray the same prayer – How long, Lord? - our pleas of distress are added to the generations upon generations who have prayed this prayer.

How long, Lord?

Forever?

How long will we sit idly by while the byproducts of the racial segregation we tolerate Monday through Saturday stares us in the face on Sunday? [v]

How long, Lord?

How long will we ignore the systemic inequalities we allow to be embedded in nearly everything we do? From driving a car or shopping at Target to presumptions of innocence or guilt, our skin color predetermines initial encounters with the police, strangers, friends, and family.

How long, Lord?

In addition to our holy scriptures, we will use Jemar Tisby’s book How to Fight Racism as a guiding text for the coming weeks. Tisby is “convinced that Christianity must be included in the fight against racism as a matter of responding to the past.”

As Christianity moved out of Western Europe, it forgot that from the very beginning, as the dust settled from the world’s creation, as God was assembling bones and knitting human flesh, humanity was created in the image of God.

How long, Lord, will we forget that you said, “Let us make humankind in our image, according to our likeness; and let them have dominion over the fish of the sea, and over the birds of the air, and over the cattle, and over all the wild animals of the earth, and over every creeping thing that creeps upon the earth.”[vi]

To be a courageous congregation is to take seriously that since its arrival in North America, the Church has been established on the backs of black and brown bodies thanks to a legal document produced by Christ’s body. Issued by Pope Alexander VI, Papal Bull Inter Caeterea (cet-era) (1493) predates the arrival of the first enslaved persons in North America (1619) and set the tone for how our nation, communities, and churches were formed. This document asserted the rights of European Spanish Christians to colonize, convert, and enslave, all in the name of Christ. The document also justified enslaving Africans and transporting them across the Atlantic, tearing families apart and setting the stage for generations of enslavement and trauma.

So, before the pilgrims landed at Plymouth Rock in search of religious freedom, before the church and state were separated by the Continental Congress, and before John Wesley rode his circuit, the church in North America grew, evangelized, and converted, forgetting that all of us – spanning race, geography, and time – are created in the image of God. Imago Dei.

How long, Lord?

Part of the lament we lift about our role – active and passive – comes when the veil of ignorance is lifted from our eyes. The lifting of this veil is a continuation of the transfiguring work of God.

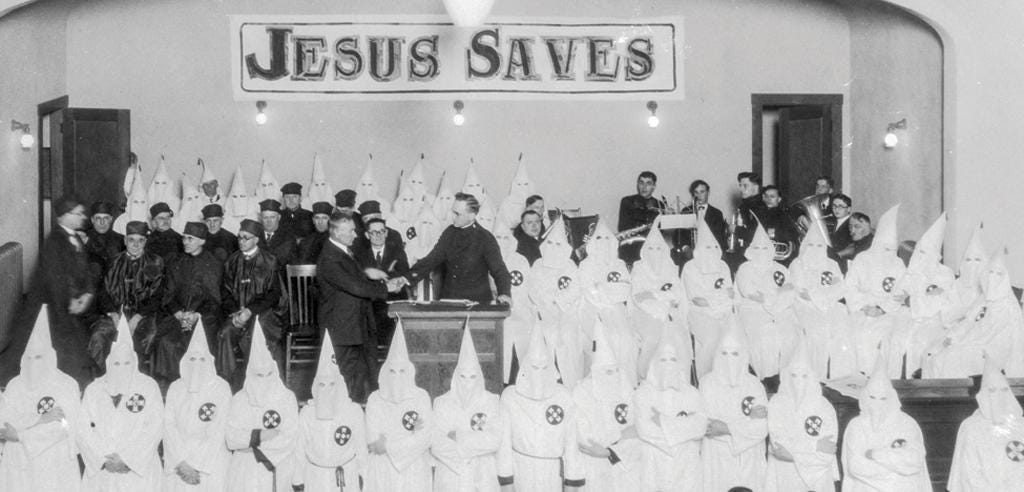

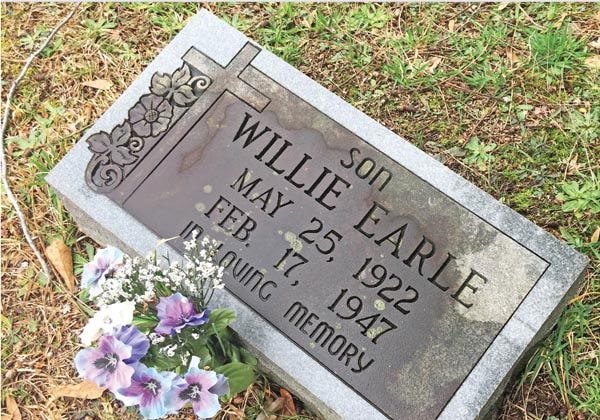

Growing up in the rural south, United Methodist Bishop Will Willimon did not know that his hometown of Greenville, SC, was at the heart of racial tension in the south. After leaving home and arriving at Wofford College, during a meeting with an academic advisor, Willimon learned of the lynching of Willie Earl. Earl was dragged from his jail cell by vigilante cab drivers guided by racial hatred and was killed, and executed in what James Cone describes as the modern-day equivalent of being nailed to a cross. If you were wondering, the Earl’s killers were not convicted.

“That’s, er, awful,” Willimon said upon hearing the story kept from him by family members, friends, and a community unwilling to come to grips with its past.

“That there was a lynching? Or awful that they never told you that folks in your hometown did it.” his advisor replied.[vii]

How long, Lord?

How long will the shock of removing the veil of ignorance continue? How long will our ignorance continue?

“Psalm 13 is the cry of black Americans.” writes Jesuit priest Mario Powell. “We have been crying out this question for centuries”, he continues “But we cannot cry it alone anymore. Until you grow close to our suffering, until it fills your eyes and ears, your minds and hearts, until you jump up on the cross with black Americans, there can be no Easter for America.”[viii]

The difficulty of prayers of lament is that we can feel as though the Good News of Jesus Christ – the Easter celebration – is as far away as the day when Rev. Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr.’s dream becomes a reality.

The Good News is the object of our prayers and lamentations is the One who made the shadow-laden journey to the cross, and when death, the consequence of our sin, seemed to have won the day, asked Mary, “why are you crying? Who are you looking for?”[ix]

The help we expect, the help we so desperately need, does not come from ourselves. The track record of human history tells this to be true, and yet time and time again, we turn to ourselves to make right that which we continue to taint with our sin. Cries of lament are our turning toward God, acknowledging our humanness, and opening ourselves to being transformed. It is in being transformed that we can act first by setting aside empty platitudes like “racism is too much, we have to give it to God,” and second, by actively working to correct generations of harm that was done in Christ’s name through acts of supposed mercy and compassion. The very things the Church has been called to do since the disciples were first called away from their fishing nets.

The transformation that comes, the coming reality of Dr. King’s dream, the fulfillment of the Kingdom of God, the Kin-dom[x] of God, is a gift to us by the One to whom we pray, the One who is actively working to transform his body, and the One who assures us we are never beyond the reach of God’s grace.

How long, Lord?

[i] Psalm 13:1-2

[ii] Psalm 13:1-13

[iii] https://reflections.yale.edu/article/resistance-and-blessing-women-ministry-and-yds/lament-and-hope-defying-hot-mess

[iv] In Psalms: The Prayer Book of the Bible Dietrich Bonhoeffer wrote, “No individual can repeat the lamentation of the Psalm out of their own experience; it is the distress of the entire community at all times” which unfolds.

[v] Jemar Tisby writes, ”the racial segregation we see on Sunday is downstream from the racial segregation we tolerate Monday through Friday. As such, fighting racism has to be something that goes beyond a once-a-week service. It must become habit, practice, and disposition.”

[vi] Genesis 1:26

[vii] In Who Lynched Willie Earl, Willimon tells the story of growing up in the rural south and guides preachers in how to see ”American racism is an opportunity for Christians to honestly name sin and engage in acts of ’detoxification, renovation, and reparation.’”

[viii] https://www.americamagazine.org/faith/2020/06/03/how-long-o-lord-psalm-13-cry-black-americans

[ix] John 20:15, NRSV

[x] Using “Kin-dom” in place of “Kingdom” is my attempt to be open to being transformed, understanding that the word “Kingdom” is laden with baggage and harm that I am beginning to understand. I guess you could say the veil is being removed.

Share this post