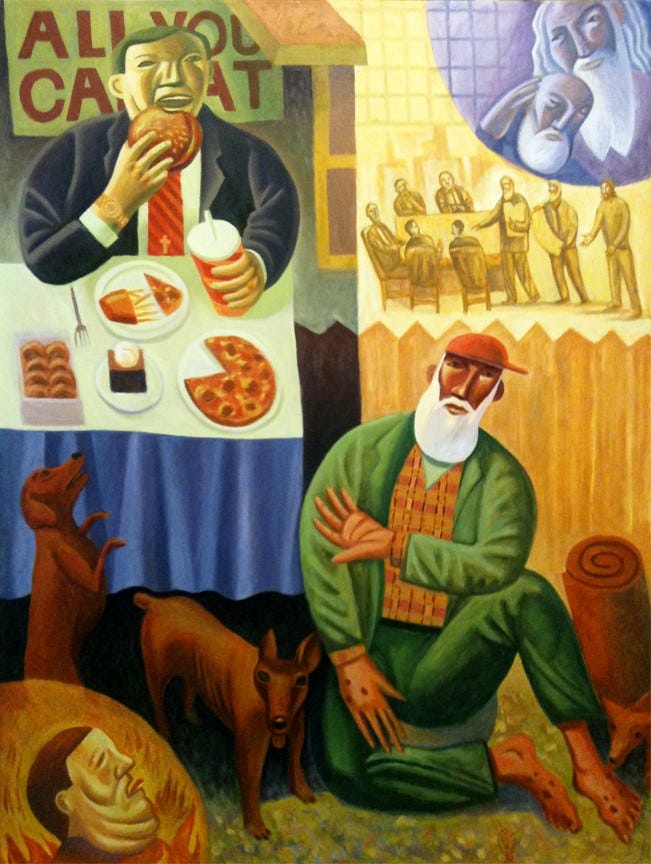

Jesus tells a story of two men: one rich, one poor. One is clothed in the finest garments and feasts daily, while the other is covered in sores, scavenging for scraps, and comforted only by dogs. This image of disparity is a stark portrayal of the world we have built—a world where the powerful flourish while the weak suffer in silence.

None of this is news to us. The chasm between rich and poor is an unrelenting reality, a construct of our own making. We dress it up with justifications, calling it the "real world," but the truth is, it’s merely the world we have designed, not the one God intends. In God’s world, the balance is overturned. The great distance we have placed between us in life is met with a divine reversal in death: Lazarus is lifted up, and the rich man is brought low.

The parable is a story about gaps, about distances fixed first by human greed and then by divine justice. It is unsettling, especially when the gap between the wealthy and the poor has grown wider than ever. We live in an age where billionaires amass wealth beyond imagination while countless Lazaruses lie at the gate, waiting for crumbs that never fall. And yet, the greatest irony of our time is that some of these modern-day rich men, like President Trump and Elon Musk, wield their wealth not to close the gap but to widen it—shutting down the government agency meant to provide aid to the very people Jesus identifies with. The wealthiest man in the world, rather than using his resources to uplift those in need, actively dismantles structures designed for humanitarian aid, further entrenching the very chasm that Jesus condemns in this parable.

Divine justice, as seen in this parable, is not arbitrary but is deeply rooted in God’s consistent concern for the poor and oppressed throughout Scripture. The prophets repeatedly warn against the accumulation of wealth at the expense of others (Isaiah 10:1-3, Amos 5:11-12), and Jesus himself declares in the Beatitudes that the poor will inherit the kingdom of God (Luke 6:20-21). The reversal in this parable aligns with God’s broader vision of justice—a justice that doesn’t simply punish the rich for their excess but seeks to establish a world where the poor are lifted up, where gaps are closed rather than widened. It reminds us that the kingdom of God is not just a spiritual ideal but an economic and social reality that demands transformation in the present.

Robert Capon helps us see the scandal of grace at work in this parable. "For Jesus came to raise the dead. He did not come to reward the rewardable, improve the improvable, or correct the correctable; he came simply to be the resurrection and the life of those who will take their stand on a death he can use instead of a life he cannot."[i] The rich man, in his self-sufficiency, refused to see his own need for grace. He believed in his wealth. The world honors winners, the self-sufficient, the successful. But Jesus honors the losers, the ones who have nothing to give, the ones who, like Lazarus, embrace a death that God can use rather than a life that serves only itself.

Capon explains, "Death-resurrection stands forth as clearly in this parable as it does in any of the others. And the successful life is just as roundly condemned. Lazarus starts out as a loser, plays out his allotted hand, and then, in one stunning throw, wins the game with the last trump of an accepted death. The rich man starts out as a winner, but because he never accepts death, he loses, hands down."[ii] The rich man was a winner in every sense—until he wasn’t. He never embraced the one truth that could have saved him: the death-resurrection reality that Jesus embodies. Lazarus, on the other hand, starts out as a loser, plays the only hand he has, and then, in one stunning reversal, wins everything. This isn’t just about the afterlife; it’s about how we live now. Do we cling to the illusion of control, of wealth, of success? Or do we die to those illusions so that we might truly live?

The chasm between them, created first by human selfishness, is now fixed by God’s justice. And in this, Jesus invites us into a different kind of existence—one that does not wait for the afterlife to correct what is broken but actively works toward resurrection now. The parable leaves us with a choice. Will we continue to live in the world we have made, a world that blesses the powerful and ignores the suffering? Or will we step into God’s world, where the first are last, the last are first, and the gaps we have created are finally and forever closed?

[i] Capon, Robert. Kingdom, Grace, Judgment: Paradox, Outrage, and Vindication in the Parables of Jesus. Eerdmans. 2002. Page 317.

[ii] Capon. Page 316,