I love to lead Chapel Time at Mount Olivet.

I carefully choose a scripture based on what is happening at the school - themes or holidays - and then go to work carefully creating a script that not only shares the amazing grace of God but also, makes our time together fun.

Last week, as the kids sat on the hard-wooden Peppy Le Pews and I read them a story about how we love one another and ourselves and then connected that story to the Bibles placed in front of them (those boring looking books, I told them, are the story of how much God loves you) one of the children asked, “Pastor Teer, how do we know God?”

How Do We Know God?

Knowing God and then articulating such knowledge is the work theologians in and outside of the church have been working to figure out ever since Jesus walked out of the tomb.

A seemingly impossible task.

A task that can consume a lifetime.

A task that once fulfilled can change, in an instant.

“I feel closest to God,” or “God is closest to me,” are two of the most frequently used phrases I have heard during my time in pastoral ministry.

Do not get me wrong, please. I have felt God’s presence in the woods and on the beach. While hiking along the Blue Ridge Mountains I have felt the Holy Spirit’s presence. But feeling God’s presence or God’s “closeness” is not the same as knowing God. And all too often feeling God’s presence is traded for knowledge of God.

In a radio conversation written by Richard Dickenson depicting a conversation between Karl Barth and Thomas Aquinas, Dickenson (on behalf of Barth wrote:

Man cannot know God through the natural world. "At the most, nature and the natural law can be no more than a par- able of the other worlds. (You know that I distinguish between this "phenomenal" tem- poral world, and the eternal "real" world.) For mortals "God is not only unprovable and unsearchable, but also inconceivable.

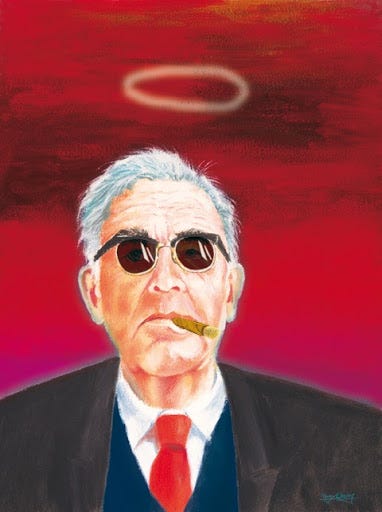

I cannot go back to the four-year-old at our next Chapel Time and quote an interpretation of Karl Barth’s theology. I can barely get away with moves like this on Sunday morning. If I held up a picture of Karl Barth and said, “Timmy, Swiss theologian Karl Barth states God is “unprovable, unsearchable, and inconceivable,” not only would the kid have no idea what I was saying, he and his classmates would think I am “coo-coo crazy” (a name Pastor Teer has been called in the past.

What am I to do?

Dickenson, on behalf of Barth, continues the conversation:

“God is thought and known when in His own freedom God makes Himself apprehensible. ... God is always the One who makes Himself known in His own Revelation, and not the one man thinks out for himself and describes as God."

We cannot know God apart from God.

God has chosen to reveal God’s self through two means to the world: the Holy Scriptures and the Word made Flesh. The Church has been entrusted with written revelation, that is continuing the revealed knowledge of God to humanity and we have the life, death, and resurrection of Jesus Christ. The Church today is sustained by God, through Word, Sacrament, and the real presence of Christ, all of which point us toward knowledge of God.

So what do we know about God?

Brian Zahnd answers this question more effectively and efficiently than anyone:

God is like Jesus.

God has always been like Jesus.

There has never been a time when God was not like Jesus.

We have not always known what God is like—

But now we do.

Understanding that God is immutable and that God like Jesus is essential to our understanding of salvation. We must not think that salvation comes about because Jesus placates God (thus changing God) or that God is obligated to satisfy retributive justice in order to forgive sin (thus making God subordinate to a higher justice). Salvation comes about because Jesus reveals the Father and does the Father’s work. Jesus tells us that the great work of the Father is to give life to the dead (see John 5 and 11). Thus the primary problem the Gospel addresses is not personal guilt (though this is included), but human subjugation to death. If we think judicial guilt is the primary problem of sin, instead of death (and then falsely imagine that God is responsible for killing Jesus instead of sinful humanity!), we greatly misrepresent the nature of salvation and concoct a distorted gospel where Jesus is saving us from God. No! Jesus reveals the Father, does the work of the Father, and saves us from the dominion of sin and death.

The Apostle Paul tells us that God was in Christ reconciling the world to himself…not reconciling himself to the world. The cross doesn’t change God (God is immutable). The cross shames the principalities and powers (exposing their claim to wisdom and justice as a naked bid for power) and changes us!

Here’s a recap: we can only know God through God’s revelation (word and flesh) and if we want to know what God is like, then we can look to Jesus, aka the Word Made Flesh.

Making Sense of Knowing God

Let’s jump back to the whole finding God in nature bit. I understand the appeal to this. I was once that guy. I spent every summer during high school in the woods - living in a tent and doing things one does in the woods. I had little time for the camp chaplain or the weekly 20-minute service he offered.

It’s not that I did not like the chaplain. In hindsight, I fondly recall Father Frankie taking the time to get to know each of the staff but my limited attention span was focused elsewhere.

Revelation (knowledge) of God does not come from nature.

Back to the conversation between Karl Barth and Thomas Aquinas.

“The only connection which remains between God and man is the analogia fidei (analogy of faith), and it is this faith which enables us to recognize the revelation rather than finding the revelation.”

Barth is arguing, sure, you might find God in nature but it has nothing with your ability to use binoculars and spot God in a tree. No, God has revealed God, you have learned something about God in nature because, as the Apostle Paul

“We are empowered and commissioned to know God in our perceptions and conception, but this knowledge - this ‘readiness by man’ - can come only from God.”

“I must still insist that there a chasm, an abyss between God and man which man can never cross, but which God has bridged for man in Jesus Christ.”

The gap between humanity and God is the consequence of our sin and that we are not our own creators. God bridges that gap in Jesus Christ and in the process revelation is constantly occurring. This is not because of our works but instead the result of grace.

Back to Chapel Time

“Pastor Teer, how do we know God?”

Well, first we know God because God wants us to know God, and because God wants us to know God, we can look to the Bible and the life of Jesus.

“What do you know about God from the stories you have heard about Jesus?” I asked the preschooler.

“Jesus loves kids,” he replied, “and you just told us that God loves us, so Pastor Teer, does that mean Jesus loves us?”

“Jesus loves all kinds of people,” I said.

“Tall, short, old, young, preschoolers, pastors, teachers, parents.”

“If you ever wonder if God loves someone the answer is always yes, because of what God has revealed to us about God’s love in the things Jesus did.”

“What about Petey?” the kid at the end of the pew shouted.

The preschooler who first asked the question and derailed Chapel Time quickly answered before I could process that there was a new question to be fielded.

“Of course, God loves Petey, because, God loves everyone and we learned that from Jesus.

“BINGO!” I shouted, “now, who wants to share their snack with Pastor Teer?”

Amen.