The moments when the world drops its mask seem to be increasing more and more these days.

Moments when the story we tell ourselves about who we are, about how safe we are, about how good we are, can no longer be maintained. Something happens. Someone is killed. And suddenly we are, all of us, exposed.

This past week, the killing of a mother in Minneapolis—by someone entrusted with authority—exposed something we work very hard not to see.[i] Not just a single act of violence, but how close violence lives to us. How easily power turns deadly. How fragile our claims of righteousness really are.

This is not about pointing fingers at a headline. It is about facing what that headline reveals. That sin is not rare. That violence is not foreign. That we are far more capable of harm than we like to admit.

These are not stories about monsters. They are revelations about us. About our bent toward self-protection. About our willingness to justify harm. About how quickly love of neighbor gives way to fear and force.

What was exposed was not simply a crime. It was us.

Our fear.

Our capacity for cruelty.

Our habit of explaining violence as if it were always someone else’s problem, always someone else’s fault.

Exposure is not comfortable. It leaves us without defenses. Without explanations that work. Without the illusion that we are better than this.

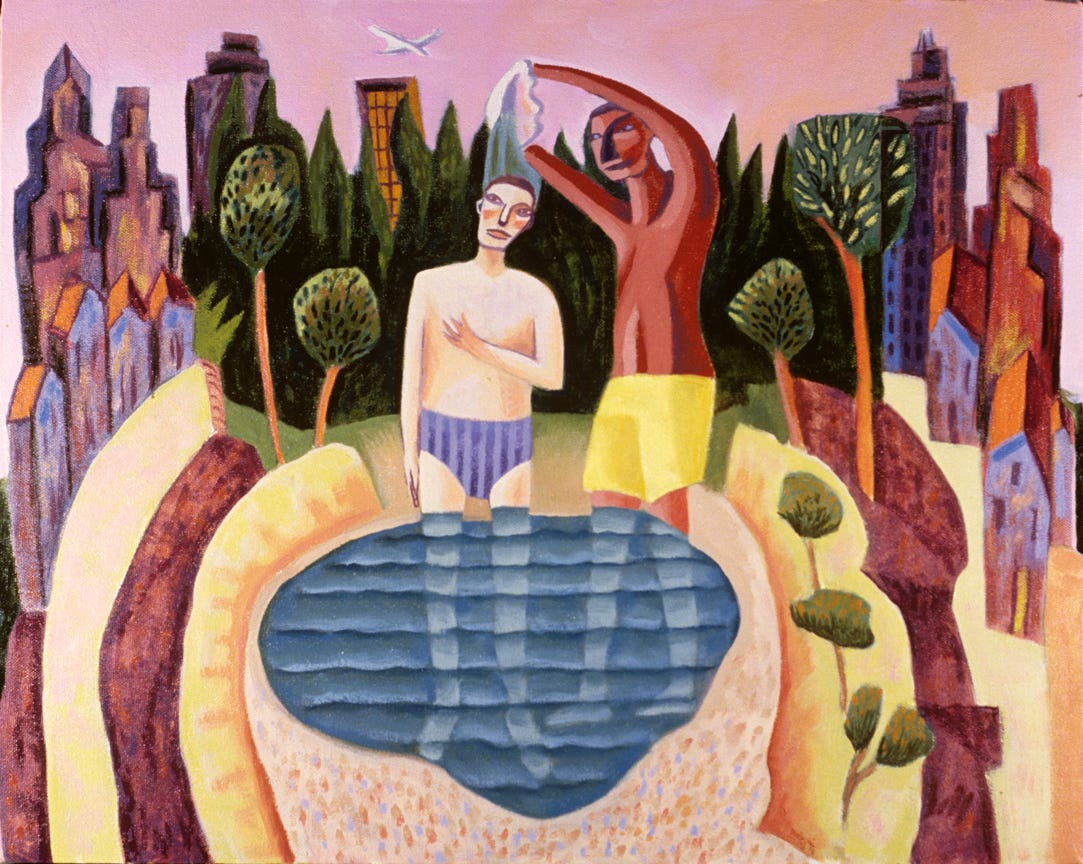

That is where baptism begins.

Not with water, but with truth.

John’s baptism in the Jordan River was not about self-improvement. It was about coming clean. People came confessing what they wished were not true. Naming what they could no longer hide. The Jordan was not a place you went to feel better about yourself. It was a place where you stopped pretending.

And then Jesus shows up.

Not to fix the system.

Not to offer commentary.

Not to remain clean.

He steps into the water meant for people who know they are not okay.

John tries to stop him. “This is backwards,” John protests. Repentance is supposed to move upward. Toward holiness. Toward improvement. But Jesus insists: “Let it be so now, to fulfill all righteousness.”

In Matthew’s Gospel, righteousness is not God demanding better behavior from a safe distance. It is God setting things right by stepping into what is broken. God’s righteousness does not hover above the mess. It enters it.

Jesus does not enter the waters of repentance because he needs them. He enters because we do. He stands where exposed people stand, so exposed people know where God stands.

The Jordan River has history. You’ll remember from Sunday school that Israel crossed this river after forty years of wandering, complaining, and second-guessing God. The Jordan River was not the end of danger. It was the end of denial. Once they crossed, they could no longer pretend they were not responsible for how they lived.

The Jordan exposes.

So does repentance—turning away from sin and toward God. Repentance names sin. It strips away excuses. It tells the truth about our bent toward violence, toward domination, toward loving ourselves more than our neighbors.

And if we follow that truth all the way through, we know where exposure leads.

Someone is killed.

Not by accident.

Not by misunderstanding.

But because violence always looks for something it can justify. Because power eventually turns on love. Because when God stands fully exposed among us, we do what we have always done.

We put Him to death.

That is the Law.

It does not flatter us. It does not let us off the hook. It tells the truth about what we are capable of, even with God in our midst.

And yet, that is not the final word spoken over us.

The heavens open.

The Spirit descends.

And a voice speaks.

“This is my Son, the Beloved.”

Not after he proves himself.

Not after he earns it.

Beloved.

That word is spoken before Jesus preaches, heals, resists temptation, or goes to the cross. Beloved is not the reward for faithfulness. It is the ground beneath it.

And then Jesus goes into the wilderness.

Baptism does not protect him from hunger, fear, loneliness, or suffering. It does not spare him the cross. What it does is tell him who he is when those things come.

That is the Gospel.

The Gospel is not that we are less violent than we feared. It is that God does not abandon us when the truth about us is revealed. God meets us there. Claims us there. Names us there.

For those who have been baptized, remembering your baptism is not sentimentality. It is identity when exposure comes. When the headlines shatter our illusions. When fear tempts us to harden our hearts. When we realize how fragile love really is.

Your baptism says there is a deeper word spoken over you. One you did not earn. One you cannot undo.

And if you have not been baptized, hear this clearly. This is not a demand. God has already stepped into the water. Baptism is not the moment God begins to love you. It is the moment your life is publicly named as already belonging to God.

Baptism does not protect us from the world.

It prepares us for it.

It prepares us to live exposed without despair.

To tell the truth without losing hope.

To face what we are capable of while trusting God’s refusal to let that be the final word.

Someone is killed.

And God still calls us beloved.

And that is the hope we cling to.

Not that our sin is small, but that it is not final.

Not that our worst days never happen, but that God does not assign them to us the way the world does—and the way we so often do to ourselves.

God names us not by what we have done, but by who we are: beloved.

That is who we are when everything else is stripped away.

Amen.

[i] https://www.nytimes.com/2026/01/07/us/ice-shooting-minneapolis-renee-good.html